Intracisternal Cranial Root Accessory Nerve Schwannoma Associated with Recurrent Laryngeal Neuropathy

Article information

Abstract

Intracisternal accessory nerve schwannomas are very rare; only 18 cases have been reported in the literature. In the majority of cases, the tumor origin was the spinal root of the accessory nerve and the tumors usually presented with symptoms and signs of intracranial hypertension, cerebellar ataxia, and myelopathy. Here, we report a unique case of an intracisternal schwannoma arising from the cranial root of the accessory nerve in a 58-year-old woman. The patient presented with the atypical symptom of hoarseness associated with recurrent laryngeal neuropathy which is noted by needle electromyography, and mild hypesthesia on the left side of her body. The tumor was completely removed with sacrifice of the originating nerve rootlet, but no additional neurological deficits. In this report, we describe the anatomical basis for the patient's unusual clinical symptoms and discuss the feasibility and safety of sacrificing the cranial rootlet of the accessory nerve in an effort to achieve total tumor resection. To our knowledge, this is the first case of schwannoma originating from the cranial root of the accessory nerve that has been associated with the symptoms of recurrent laryngeal neuropathy.

INTRODUCTION

Intracranial accessory nerve schwannomas are rare. Such tumors are divided into two main types : 1) intrajugular schwannomas located at the jugular foramen, which comprise the majority of cases, and 2) intracisternal schwannomas, which occupy the cisterna magna13,31). Although the clinical manifestations of these tumors vary depending on the tumor's location and the extent of its growth, intracisternal tumors usually present with cerebellar signs and myelopathy. Intrajugular tumors are commonly associated with specific symptoms and signs of cranial nerve dysfunction, including hearing impairment, dysphagia, and difficulty in phonation1,18,20).

We report here on a unique case of an intracisternal schwannoma arising from the cranial root of the accessory nerve in a 58-year-old woman who presented with the atypical symptom of hoarseness. In this report, we describe potential anatomical explanations for the patient's unusual clinical manifestations and discuss the safety of complete tumor resection with sacrifice of the originating nerve rootlet in terms of postoperative neurological deficit.

CASE REPORT

A 58-year-old female presented with symptoms of hoarseness and dizziness, which had begun 2 months prior. Neurological examination on admission revealed no focal neurological deficit, except for mild hypesthesia on the left side of her body. She had no significant medical or surgical history.

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging revealed a mass of 3.3×2.7×3.3 cm in the left cerebellomedullary cistern, containing both cystic and solid components (Fig. 1). The solid portion located mainly in the periphery of the tumor, but not the central cystic area, was strongly enhanced by gadolinium. The tumor compressed the medulla and cerebellum, leading to displacement of these structures. MR angiography revealed superiomedial displacement of the lateral medullary and tonsillomedullary segments of the left posteroinferior cerebellar artery.

A : Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) image showing a well-defined cystic lesion in the left cerebellomedullary cistern. B : Axial gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MR image showing enhancement in the cyst wall and inner solid components of the mass. The tumor compressed the medulla and high cervical spinal cord. C : Sagittal gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MR image showing severe impingement of the craniocervical brainstem. D : MR angiogram illustrating superiomedial displacement of the lateral medullary and tonsillomedullary segments of the left posteroinferior cerebellar artery (arrow).

Needle electromyography (EMG) performed on the bilateral cricothyroid and thyroarytenoid muscles revealed polyphasic and long motor unit potentials with reduced recruitment patterns in the left thyroarytenoid muscle, suggesting the existence of left recurrent laryngeal neuropathy. Mild vocal cord paralysis was noted on the left side upon otolaryngological examination. Based on these imaging findings and clinical manifestations, a preoperative diagnosis of lower cranial nerve schwannoma or cystic meningioma was made.

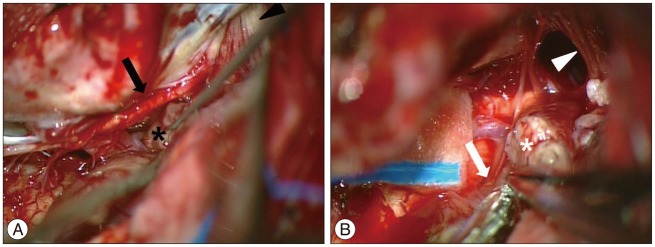

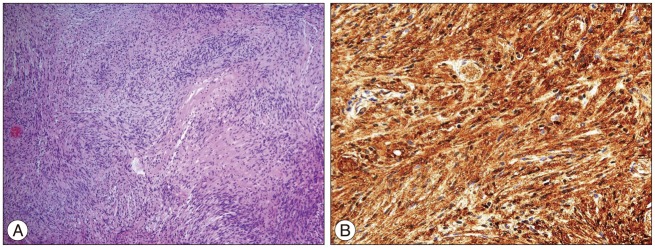

An image-guided, inferior unilateral suboccipital craniectomy with partial C1 laminectomy was performed with the patient in the prone position. After a Y-shaped incision was made in the dura, the tumor was found to be located in the left foramen magnum and cerebellomedullary cistern, extending cephalad and ventrally, towards the left cerebellar hemisphere. As expected, the high cervical spinal cord and medulla were compressed to the right and flattened. The tumor had a firm, transparent, and smooth capsule filled with yellowish cystic contents. The tumor was easily dissected away from the surrounding structures with aspiration of the cyst. The hypoglossal canal and jugular foramen were tumor free. The spinal root of the left accessory nerve was adherent to the tumor capsule, but was successfully dissected from the tumor without injury to the nerve (Fig. 2A). At the final stage of the surgery, we found that one cranial rootlet of the left accessory nerve was incorporated within the tumor near the exit zone of the rootlet in the medulla (Fig. 2B). We deduced that the rootlet was the origin of the tumor. The rootlet was cut from the proximal and distal portions of the tumor and a gross total resection was performed. After the tumor had been removed, the glossopharyngeal, vagal, and hypoglossal nerves and the spinal roots of the accessory nerve were observed to be intact. Histopathological examination revealed that the tumor was composed of hypercellular (Antoni Type A pattern) and hypocellular (Antoni Type B pattern) areas (Fig. 3A). The former area contained compact spindle cells with twisted nuclei arranged in short bundles of interlacing fascicles displaying nuclear palisading and whorls of cells. The latter areas were composed of wavy spindle cells and oval cells in a loose stroma. The tumor cells were immunopositive for S-100 and immunonegative for glial fibrillary acidic protein (Fig. 3B). The mass was confirmed to be a schwannoma.

Intraoperative photograph showing the spinal accessory nerve (arrow) was easily dissected away from the tumor (*) (A). Multiple rootlets of IX, X, and XI (arrowhead) run to the jugular foramen. The cranial root of the accessory nerve (arrow) near the brain stem incorporated into the tumor (*) (B). Intracisternal segments of the IX and X nerves are seen in the cranial side (arrowhead).

Photomicrograph showing palisading and whorling spindle cells with compact and loose areas (Antoni A and B arrangement), consistent with a diagnosis of schwannoma (H&E; original magnification ×100) (A). Most neoplastic cells are strongly positive for S-100 on immunohistochemical staining (original magnification ×400) (B).

Postoperative MR imaging determined that the tumor had been totally resected and that the compression of the medullary and high cervical spinal cord had been relieved. The patient's left side hypesthesia disappeared immediately after surgery and her hoarseness gradually improved over 6 months.

DISCUSSION

Schwannomas of the lower cranial nerves are rare and usually arise in the jugular foramen.14) In lower cranial schwannoma, the glossopharyngeal nerve is the most frequently reported site of origin, the vagus nerve is the second most common site, and the accessory nerve is the least common site of origin11,12). In their review of 91 cases of jugular foramen schwannoma, Shiroyama et al.28) reported that only three tumors arose from the accessory nerve. Similarly, when Bakar1) reviewed the literature, describing 199 cases of lower cranial nerve schwannoma, he found that only 11 tumors were identified as originating from the accessory nerve.

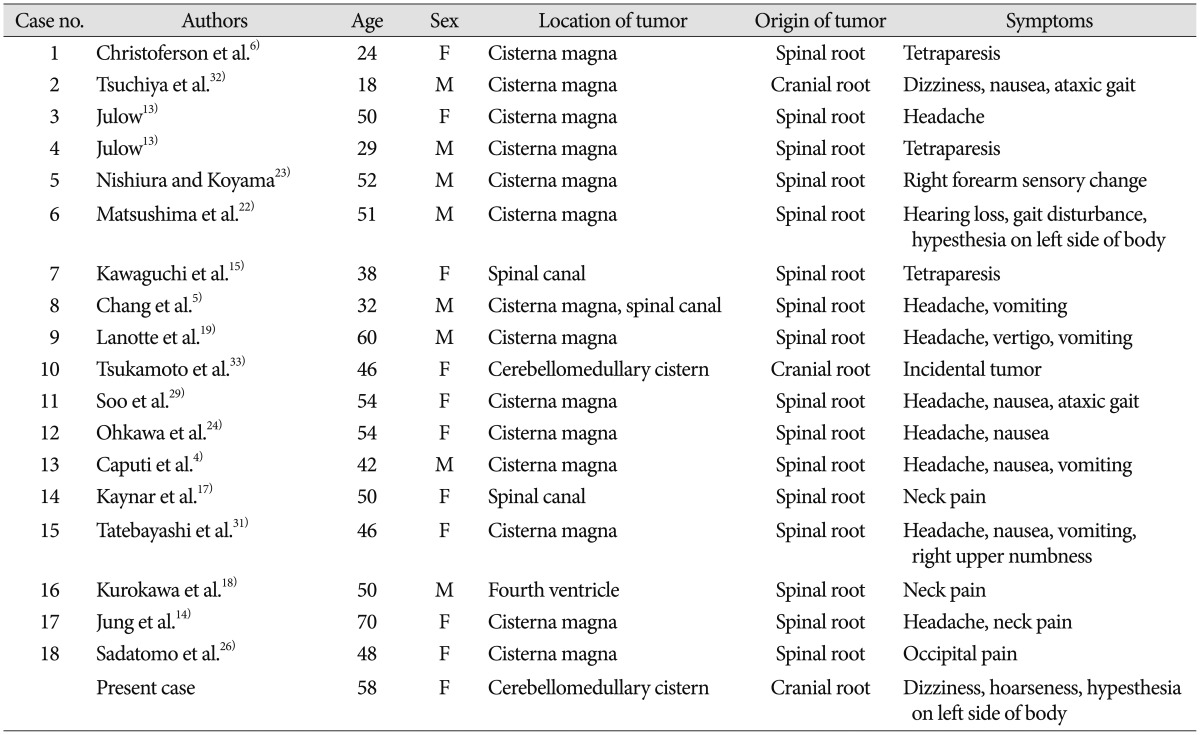

Based on the location of the tumor, Julow categorized accessory schwannomas into two types : 1) intrajugular schwannomas that grow into the jugular foramen and 2) intracisternal schwannomas that grow into the cisterna magna13). Since Christoferson et al.6) first reported an accessory schwannoma of the intracisternal type, 17 additional cases of intracisternal accessory nerve schwannoma have been recorded (Table 1)4,5,13,14,15,17,18,19,22,23,24,26,29,31,32,33). In most cases, the origin of these tumors was the spinal root of the accessory nerve, whereas there were only two cases exhibiting a cranial root origin32,33). In one of these cases, cranial root accessory nerve schwannoma was found incidentally during cerebellomedullary angle meningioma surgery33).

Intracisternal accessory nerve schwannomas usually manifest cerebellar signs and/or myelopathy associated with their direct compressive effects on the cerebellum, brain stem, and/or spinal cord. In contrast, intrajugular tumors typically present with otologic symptoms and jugular foramen syndrome, characterized by symptoms of tinnitus, hearing impairment, dysphagia, and hoarseness1,18,20). Our patient with an intracisternal tumor suffered from dizziness and hypesthesia of the body and trunk on the left side, possibly due to a mass effect on the brain stem and cerebellum. Interestingly, she exhibited hoarseness associated with recurrent laryngeal neuropathy, as diagnosed by a preoperative EMG examination. This finding is likely to be related to the unique anatomical features of the accessory nerve, which consists of both spinal and cranial components. The spinal root, which originates from an elongated nucleus extending between C1 and C7, ascends through the foramen magnum and forms the conjoined accessory nerve proper by joining with the cranial roots. The cranial roots arise from the caudal region of the nucleus ambiguus before exiting the skull through the jugular foramen2,7,25). After exiting the skull, the accessory nerve splits into two rami (internal and external) and the fibers of the cranial accessory branch (internal ramus) join the vagus nerve. They are then distributed to the periphery to innervate the palatal, pharyngeal, and laryngeal muscles via several branches, including the recurrent laryngeal nerve21,30). The larger spinal accessory branch (external ramus) innervates the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles8,9,10). Therefore, the hoarseness observed in our case was caused by dysfunction of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, which in turn was associated with the unique tumor origin in the cranial rootlet of the accessory nerve.

Because of the benign histological characteristics of most cases of lower cranial nerve schwannoma, complete surgical resection is normally the ideal goal of treatment for these tumors. However, considerable numbers of patients have experienced posto-perative morbidity following aggressive surgical resection, especially for intrajugular tumors3,16,20). The most common surgical complications are lower cranial neuropathies1,27), which can severely affect quality of life because of difficulty in phonation and swallowing. Given that these complications may require the postoperative placement of tracheostomy or gastrostomy tubes, the decision to perform a complete resection must be made in balance with the need to minimize postsurgical complications. In a recent comparative study of two surgical techniques (aggressive total resection vs. maximal safe resection) for the treatment of jugular foramen schwannomas, a more conservative resection focusing on preserving the pars nervosa provided improved surgical morbidity without a statistically significant increase in tumor recurrence27). The authors of this comparative report recommended a shifting paradigm in order to optimize patient outcomes through maximal resection with an emphasis on preservation of critical neurovascular structures.

In contrast with the standard treatment for intrajugular schwannomas, more aggressive resection, which includes the nerve roots of origin, is preferred for intracisternal spinal root accessory nerve schwannomas, because sacrifice of a spinal accessory nerve root rarely results in new postoperative neurological deficits18). A recent postmortem study revealed that motor fibers derived from C2 to C4 innervate the trapezius muscle in addition to the spinal accessory nerve34), a fact that may explain the maintenance of trapezius function following spinal accessory nerve resection.

However, definitive evidence regarding neurological complications due to sacrifice of the cranial root is lacking, because of the extreme rarity of cranial root accessory nerve schwannomas. In the present case, we achieved total tumor resection by excising the rootlet on both sides of the tumor without provoking any new neurological signs. Similarly, Tsukamoto et al.33) also reported en block tumor resection including origin nerve rootlet, cranial root of accessory nerve, without postoperative additional deficit. Vagus nerve consists of two components : one is cranial root fibers of the accessory nerve and the other is vagal root fibers originating from the upper part of the nucleus ambiguous. The latter is the major component of the vagus nerve. It is therefore reasonable to believe that sacrificing the cranial rootlet of the accessory nerve to achieve total tumor resection may not lead to critical dysfunction of the vagus nerve. Future anatomical studies are required to fully clarify and confirm the safety of this procedure and ensure the postoperative preservation of normal pharyngeal and laryngeal function.

CONCLUSION

To our knowledge, this report is the first to describe a case of accessory nerve schwannoma that originated from a cranial rootlet and produced recurrent laryngeal neuropathy. The case presented here indicates that total removal of intracisternal-type schwannomas that have originated from the cranial root of the accessory nerve can be achieved with a good outcome.