Metastatic Brain Neuroendocrine Tumor Originating from the Liver

Article information

Abstract

A 67-year-old male presented with left temporal hemianopsia and left hemiparesis. A contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance image revealed a 4.5×3.5×5.0 cm rim-enhancing mass with central necrosis and associated edema located in the left occipital lobe. Of positron emission tomography and abdominal computed tomography, a 9–cm mass with poor enhancement was found in the right hepatic lobe. Craniotomy and right hemihepatectomy was performed. The resected specimen showed histological features and immunochemical staining consistent with a metastatic neuroendocrine tumor (NET). Four months later, the tumors recurred in the brain, liverand spinal cord. Palliative chemotherapy with etoposide and cisplatin led to complete remission of recurred lesions, but the patient died for pneumonia. This is the first case of a metastatic brain NET originating from the liver. If the metastatic NET of brain is suspicious, investigation for primary lesion should be considered including liver.

INTRODUCTION

In patients with neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), the incidence of brain metastasis is rare, with estimates between 1.5–5%4). NETs of the liver are extremely rare. To our knowledge, this is the first case of primary hepatic NET with brain metastasis.

Clinical diagnosis of metastatic brain NETs is usually difficult because of the rarity of the tumor and the difficulty of differentiating it from other brain tumors like glioblastoma multiforme through imaging study. Since the prognosis of glioblastoma multiforme is poor due to its high-grade status, prompt surgery for pathologic confirmation and resection is warranted216). And if the NET of brain is confirmed, investigation for primary lesion should be considered including liver.

CASE REPORT

History and examination

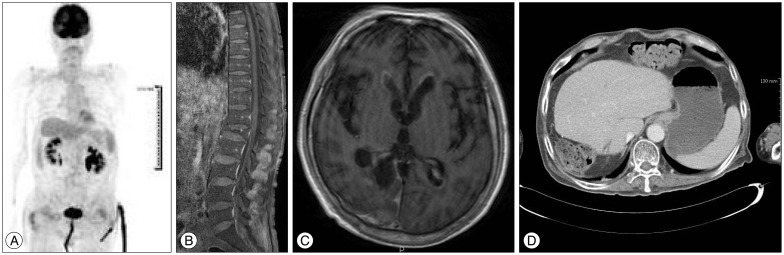

A 67-year-old male presented with headache, left temporal hemianopsia and progressive left hemiparesis beginning 10 days prior. Physical examination revealed decreased upper arm motor power to grade IV and lower leg power to grade II. A T1-weighted image from a contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed a 4.5×3.5×5.0 cm rim-enhancing mass with central necrosis and associated edema located in the right occipital lobe (Fig. 1A).

A : Axial, T1-weighted, post-gadolinium image of the brain. B : Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT). C : Axial, T1-weighted, post-gadolinium image of the liver. Note a rim-enhancing mass with central necrosis and associated edema in the right occipital lobe of brain and right hepatic lobe.

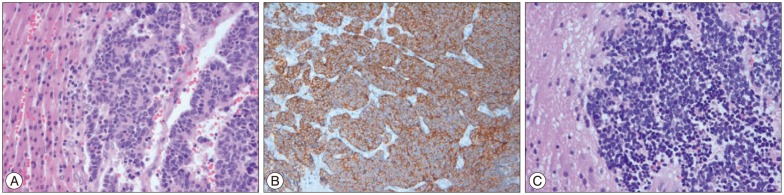

Operation

The patient underwent a craniotomy for diagnosis and symptom relief. Histological features and immunohistochemistry of the tumor were consistent with a metastatic NET. The tumor cells were positive for CD56, synaptophysin (Fig. 2) and negative for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). There was necrosis with 50% of Ki-67 labeling index, so it was considered a poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (G3 by 2010 WHO classification). Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) and liver MRI confirmed the presence of a 9×10×8.5 cm mass in the right hepatic lobe (Fig. 1B, C). The specimen of the sono-guided liver biopsy demonstrated the same histological findings as the brain lesion. We could not find another primary focus, so we concluded that the patient had primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma with brain metastasis. Right hemihepatectomy with cholecystectomy was then performed. The tumor size was 10×10 cm with neuroendocrine tumor, and the resection margins were negative.

Adjuvant treatment

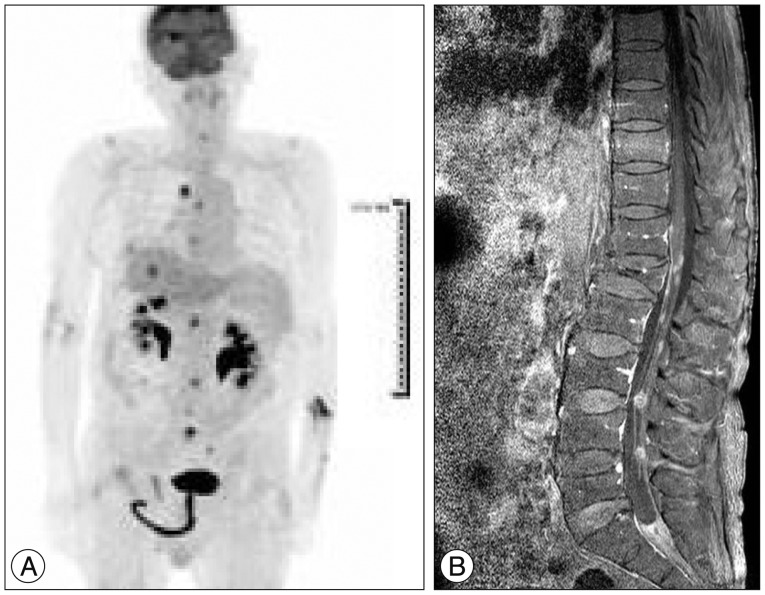

Then the patient was followed on a regular basis in outpatient clinic. About 4 months after craniotomy, the patient complained of progressive left-sided weakness. Restaging was performed. Brain-enhanced MRI revealed a suspicious recurrence in the right occipital lobe and right inferior aspect of the cerebellum (Fig. 3A). Enhanced CT of the abdomen revealed a suspicious recurrence in segment 8 of the liver (Fig. 3B). We resected the recurrent tumor mass in the right occipital lobe to relieve the progressive neurologic symptoms. The patient then received postoperative cranial radiation. After radiation therapy, he complained of bilateral leg weakness. PET-CT scan and spine-enhanced MRI showed multifocal FDG uptake in the thoracic and lumbar spinal cord (Fig. 4). We decided to recommend palliative chemotherapy with etoposide and cisplatin. The chemotherapy was delivered every 28 days with the following regimen : on day 1, etoposide 100 mg/m2 over 1 hour I.V. infusion; on days 2 and 3, etoposide 100 mg/m2 over 1 hour I.V. infusion and cisplatin 45 mg/m2 over 24 hour I.V. infusion. About two months after the third cycle of etoposide and cisplatin chemotherapy, PET-CT, brain-enhanced MRI, spine-enhanced MRI and abdomen-enhanced CT showed complete remission of the previously enhancing tumor (Fig. 5). Unfortunately, paralysis of the lower extremities was not improved. About 3 weeks after discharge, the patient was readmitted for fever and purulent sputum. Despite intensive treatment including ventilator care, the patient died after 1 month from pneumonia.

A : Axial, T1-weighted, post-gadolinium image of the brain. B : Abdomen enhanced CT at 4 months after first craniotomy and hepatectomy. Note suspicious recurrence in the occipital lobe, inferior right cerebellum, and segment 8 of the liver.

A : PET-CT scan after whole-brain radiation therapy. Note the multifocal FDG uptake in the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spinal cord and malignant tumor in right hepatectomy state. B : Spine post-gadolinium image. Note metastasis along the meninges at the T12–L1 level and cauda equine along the lumbar spine.

DISCUSSION

Among NETs, primary hepatic NETs are extremely rare356). As the liver is the most frequent metastatic site for NETs, the differential diagnosis between NET and metastatic hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma is often difficult and debatable11114). In previous studies, NETs occur most often in middle-aged and female patients. The most common presenting symptom is abdominal pain, and about 5% of patients present with typical carcinoid syndrome610).

Usually, the prognosis of a poorly differentiated NET is very poor, with a median survival of approximately 6 months without therapy81315). In 1991, Moertel et al.12) reported an overall response rate of 67% (17% complete remission, 50% partial remission), with a median progression-free survival of 8 months and a median overall survival of 19 months in 18 patients diagnosed with undifferentiated NETs.

Until now, the treatment of choice for localized, primary hepatic NET is hepatectomy917). Surgical resection of a primary liver tumor is necessary for symptom relief by cytoreduction and possible cure. As in this case, one could consider metastectomy of the brain for both diagnosis and treatment if the brain lesion is resectable. For patients with NETs and multiple masses or distant metastases, chemotherapy is an option. According to the one study of primary NETs arising from the hepatobiliary and pancreatic regions, a response rate of 14% and median survival of 5.8 months were obtained in response to combined etoposide plus cisplatin therapy7).

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, if the brain imaging of the patient has the possibility of metastasis, systemic evaluation is warranted. This case is first report for the primary liver NET with brain metastasis. We should remember that brain NET should be confirmed by pathology, and rarely liver NET could be primary.