INTRODUCTION

The incidence of spontaneous thrombosis of cerebral aneurysm is about 1-2% of ruptured aneurysms7). Spontaneous thrombosis of cerebral aneurysm is considered as a hemodynamically unstable status, and the natural history of giant or large aneurysm has been suggested (growth, recanalization, and even rupture or thromboembolic event)3,5,6,16). However, the reports on recanalization of small aneurysm after spontaneous thrombosis are rare, and the natural history is still unknown.

We present two cases of spontaneous thrombosis and recanalization of small saccular aneurysms, and suggest a presumed mechanism, and its clinical significance23).

CASE REPORT

Case 1

A 52-year-old woman presented to the emergency room with a sudden-onset stuporous mentality. The medical history was significant for hypertension and diabetes, for which the patient was taking oral medications. In addition, the patient was suffering from angina, and was taking 100 mg of aspirin daily.

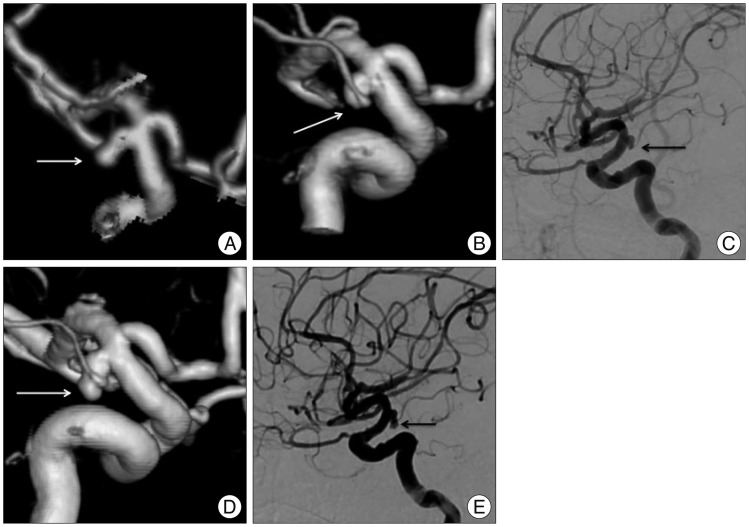

Brain computed tomographic (CT) scans revealed a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) at the basal cistern and both sylvian fissures, mainly on the left side. Three-dimensional (3D) CT reconstruction revealed an aneurysm at the basilar bifurcation and at left anterior choroidal artery. The basilar bifurcation aneurysm was 10├Ś10 mm in size, with a broad neck (9 mm). The left anterior choroidal artery aneurysm was 3├Ś6 mm in size, with an irregular shape (Fig. 1A). Based on the distribution of the hematoma and the shaped of aneurysms, we considered the left anterior choroidal artery aneurysm to be ruptured and decided to perform an emergency endovascular coil embolization on the day of admission.

Under general anesthesia, we performed induced hypotension below 60 mm Hg of mean arterial pressure. Baseline cerebral angiography revealed that the left anterior choroidal artery aneurysm had decreased in size compared to that found in the 3D angiography (Fig. 1B, C). Additionally, we could not observe contrast filling from the distal part of the aneurysm. Because partial occlusion of the aneurysm might increase the risk of rebleeding after thrombolysis, we decided not to perform coil embolization14). Also, given the patient's conditions (aspirin medication and pulmonary edema combined with pneumonia), we could not perform aneurysm clipping at early stage.

Follow-up angiography 7 days later demonstrated complete recanalization of the distal part of the aneurysm (Fig. 1D, E). Accordingly, we performed surgical clipping, and the patient recovered and was discharged with a Glasgow outcome scale (GOS) score of 5.

Case 2

A 58-year-old man was admitted to our neurosurgical department for the evaluation of headache and dizziness that occurred several months earlier. The patient's past medical history was unremarkable. On admission, the patient had no neurological signs or abnormal hematological findings including coagulation time.

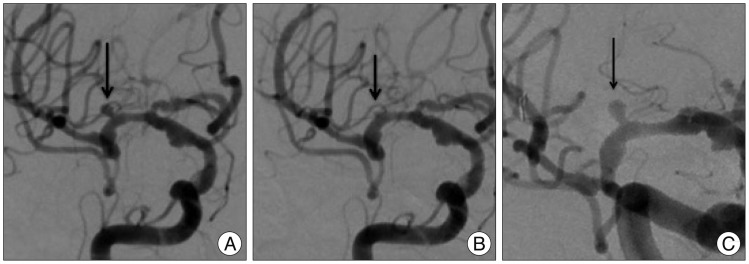

Brain 3D CT angiography revealed a 3├Ś1.7 mm aneurysm in the basilar bifurcation, and a 3├Ś1.5 mm aneurysm in the proximal middle cerebral artery (MCA). We decided to perform endovascular coil embolization with consent from family members.

Under general anesthesia, we performed endovascular coiling. Baseline angiography revealed small aneurysm in the proximal MCA (Fig. 2A). We placed a guiding catheter into the proximal internal cerebral artery, and the microcatheter was placed in the proximal MCA. Subsequent road map and angiography revealed complete disappearance of the right MCA aneurysm without evidence of vasospasm (Fig. 2B). Therefore, we only performed a coil embolization of the basilar bifurcation aneurysm.

The follow-up angiography 48 days later confirmed complete recanalization of the right MCA aneurysm (Fig. 2C). We performed coil embolization without any complications.

DISCUSSION

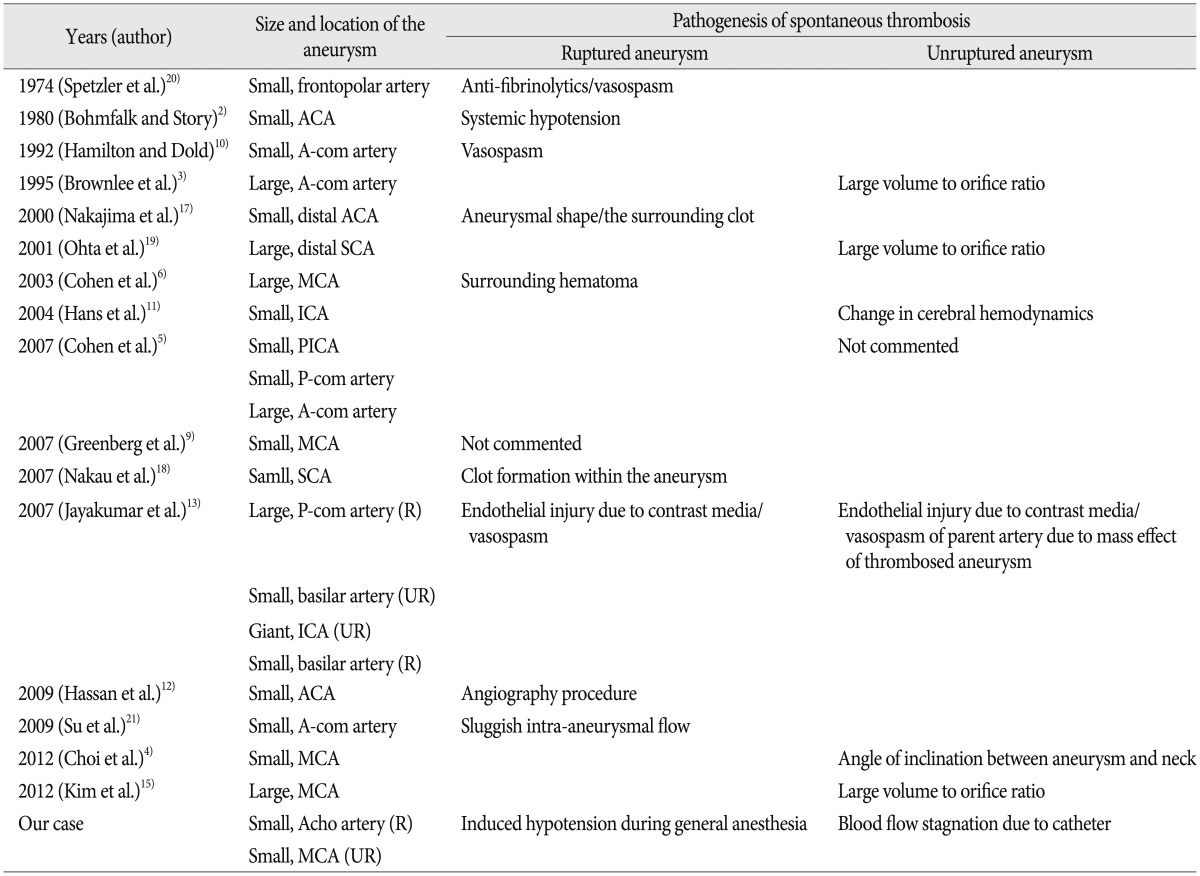

Several mechanisms have been reported to contribute to spontaneous thrombosis of cerebral aneurysms. We show a summary of reported cases of spontaneous thrombosis (Table 1). It is well known that spontaneous thrombosis in giant or large aneurysm is related to the ratio of aneurysm volume to neck size, as have been demonstrated in an animal model of aneurysm1). The blood flow within giant or large aneurysms is slow and turbulent, which may induce spontaneous thrombosis3).

However, hemodynamic or local factors seem to be more important in spontaneous thrombosis of small aneurysms. Spetzler et al.20) reported a case of small aneurysm that disappeared and reappeared. They did refer to the possible effect of anti-fibrinolytic agent or vasospasm. The angiographic procedure itself has been also proposed. Non-ionic contrast media has been reported to have thrombogenic potential8). Systemic hypotension was postulated as a potential mechanism for spontaneous thrombosis2). Nakajima et al.17) suggested aneurysmal shape and the surrounding clot as putative factors related to the intermittent appearance of the aneurysm.

In this report, we were uncertain as to the mechanism of spontaneous thrombosis in these small aneurysms, but have considered two possibilities. Induced hypotension under general anesthesia might have played some role in the spontaneous thrombosis. We usually adopt systemic hypotension (mean arterial pressure below 60 mm Hg) after the induction of general anesthesia in the patient with ruptured intracranial aneurysm. We presumed that sudden decrease of blood pressure might result in circulatory delay and spontaneous thrombosis of ruptured aneurysm under increased intracranial pressure. Bohmfalk and Stroy2) postulated systemic hypotension as a possible mechanism for angiographic disappearance of aneurysm. The other was the result of blood flow stagnation from the microcatheter during endovascular procedure. In case 2, spontaneous thrombosis occurred before the selection of the aneurysm by microcatheter and microguidewire. Also, there was no angiographic evidence of vasospasm. Accordingly, we presumed that blood flow stagnation due to the microcatheter caused spontaneous thrombosis in small aneurysm. Szajner et al.22) suggested vasospasm in addition to flow arrest from microcatheter and microguidewire during coli embolization as a possible etiology of spontaneous thrombosis in small aneurysms.

In summary, spontaneous thrombosis in ruptured small saccular aneurysms may attribute to anti-fibrinolytic agent, vasospasm, systemic hypotension, surrounding clot, and contrast media. The contrast media and blood flow stagnation may be possible etiologies in unruptured cases. Especially, spontaneous thrombosis of ruptured small aneurysms may occur during the early period after SAH and could be recanalized within the next few weeks9,17).