Clinical Outcomes of Spontaneous Spinal Epidural Hematoma : A Comparative Study between Conservative and Surgical Treatment

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The incidence of spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma (SSEH) is rare. Patients with SSEH, however, present disabling neurologic deficits. Clinical outcomes are variable among patients. To evaluate the adequate treatment method according to initial patients' neurological status and clinical outcome with comparison of variables affecting the clinical outcome.

Methods

We included 15 patients suffered from SSEH. Patients were divided into two groups by treatment method. Initial neurological status and clinical outcomes were assessed by the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) impairment scale. Also sagittal hematoma location and length of involved segment was analyzed with magnetic resonance images. Other factors such as age, sex, premorbid medication and duration of hospital stay were reviewed with medical records. Nonparametric statistical analysis and subgroup analysis were performed to overcome small sample size.

Results

Among fifteen patients, ten patients underwent decompressive surgery, and remaining five were treated with conservative therapy. Patients showed no different initial neurologic status between treatment groups. Initial neurologic status was strongly associated with neurological recovery (p=0.030). Factors that did not seem to affect clinical outcomes included : age, sex, length of the involved spinal segment, sagittal location of hematoma, premorbid medication of antiplatelets or anticoagulants, and treatment methods.

Conclusion

For the management of SSEH, early decompressive surgery is usually recommended. However, conservative management can also be feasible in selective patients who present neurologic status as ASIA scale E or in whom early recovery of function has initiated with ASIA scale C or D.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of spinal hematoma is rare, and epidural hematomas are the most common type of this disease19). Spinal epidural hematomas are divided into two subgroups; spontaneous spinal epidural hematomas (SSEH) and traumatic spinal epidural hematomas. The incidence of SSEH is estimated to be 0.1 per 100000 patients per year15). The clinical presentation is usually characterized by the acute onset of back or neck pain with rapidly progressive neurological deficits due to the compression of the spinal cord or spinal nerve roots.

Since a severe neurologic deficit is accompanied with SSEH, rapid diagnosis and treatment is important. As reported in the literatures, the primary treatment option is decompressive surgery but the number of reports regarding spontaneous resolution of SSEH has increased8,10,12,26-28). However, evidence based arguments for choosing the optimal treatment method have not yet been established. We tried to describe the adequate method of treatment according to the analysis of patients' neurological status and assess clinical outcome and prognostic factors by the comparison of variables affecting the clinical outcome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Retrospectively, 15 patients with spontaneous spinal epidural hematomas between 2004 and 2012 were included in the study. We reviewed the patients' medical records and image studies under approval of institutional review board.

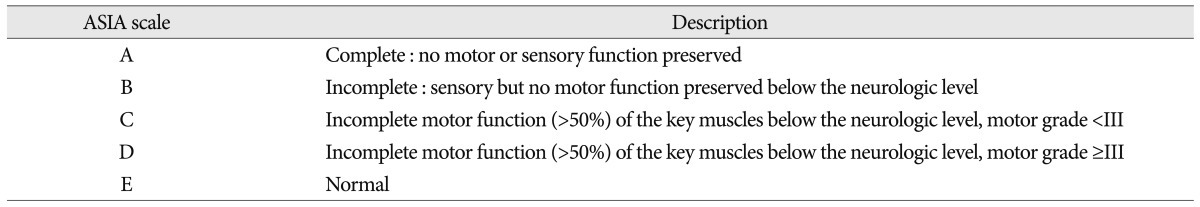

Initial neurologic status and clinical outcome was assessed by the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) impairment scale (Table 1)24). The hematoma location was assessed by magnetic resonance (MR) axial image. According to relative position to the spinal cord, sagittal location was classified as anterior and posterior. The involved segment was defined as present hematoma between center level of upper and lower discs by MR sagittal image. The duration of hospital stay was calculated with admission and discharge date. All of premorbid medications were identified using prescriptions.

Nonparametric statistical techniques were used to overcome the small sample size. And subgroup analysis according to clinical outcomes regardless initial neurological status and method of treatment was also carried. Continuous evaluated parameters were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test, and the categorical data were analyzed with the Fisher's exact test and Linear-by-Linear Association test. p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

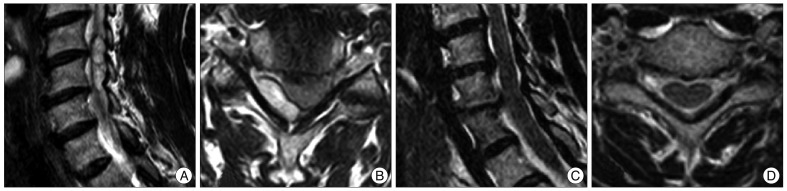

There were four male and eleven female patients and their median age was 63 years. The patients were divided into two groups, one with surgery and the other with conservative treatment. Decompressive laminectomy (n=6), hemilaminectomy (n=3) and cervical laminoplasty (n=1) with hematoma evacuation were performed in surgically treated patients. Conservatively treated patients received 10 mg of dexamethasone over an intravenous line after admission. One patient was excluded since he presented without neurologic deficits other than pain. Until motor weakness was improved, 4×4 mg of dexamethasone was administered over an average time range of two days. The dose of steroid was then slowly tapered off during five to seven days (Fig. 1).

T2 oblique sagittal (A) and axial (B) MRI of a patient treated with conservative management. T2 oblique sagittal (C) and axial (D) magnetic resonance images after a 1-month follow-up demonstrate the disappearance of the epidural hematoma.

Two (13.3%) patients had SSEH at the cervical spine; five (33.3%) at the cervicothoracic junction; four (26.7%) at the thoracic spine; and four (26.7%) at the thoracolumbar junction. Twelve (80.0%) patients manifested epidural hematomas located posteriorly to the spinal cord. Only three (20.0%) had anteriorly located SSEH. Table 2 showed the summarized cases.

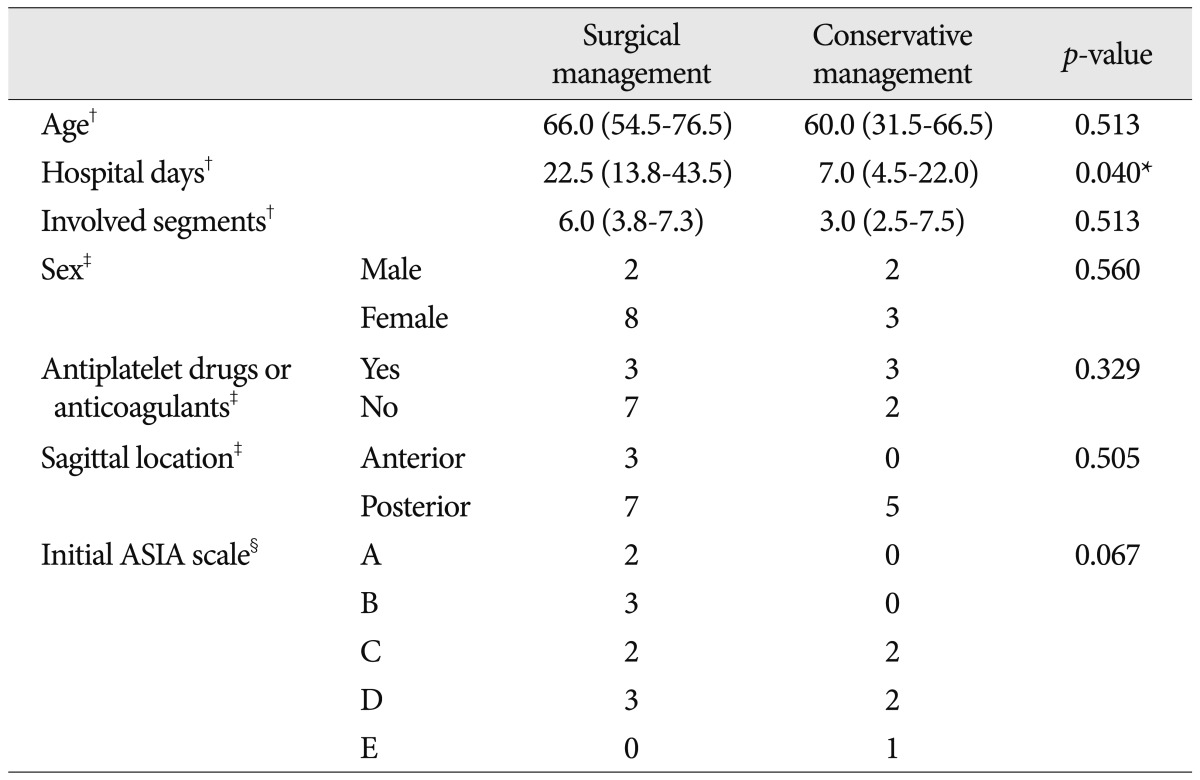

There were no statistical differences in age, sex and the number of the involved vertebral segments determined by MR imaging between the two groups. The surgically treated group showed tendency of poorer initial neurologic status as determined by the ASIA scale without a statistically significant difference (p=0.067). And the period of hospitalization was longer in the surgically treated group (p=0.040). Three patients (30.0%) in the surgical management group and three (60.0%) in conservative treated patients took antiplatelet drugs or anticoagulant therapy, without statistically significant differences. All conservatively treated patients and seven (70.0%) out of ten patients in the surgical group presented posteriorly located hematomas. Table 3 shows these results from the comparison of variables in relation to treatment methods.

Subgroup analysis according to clinical outcomes

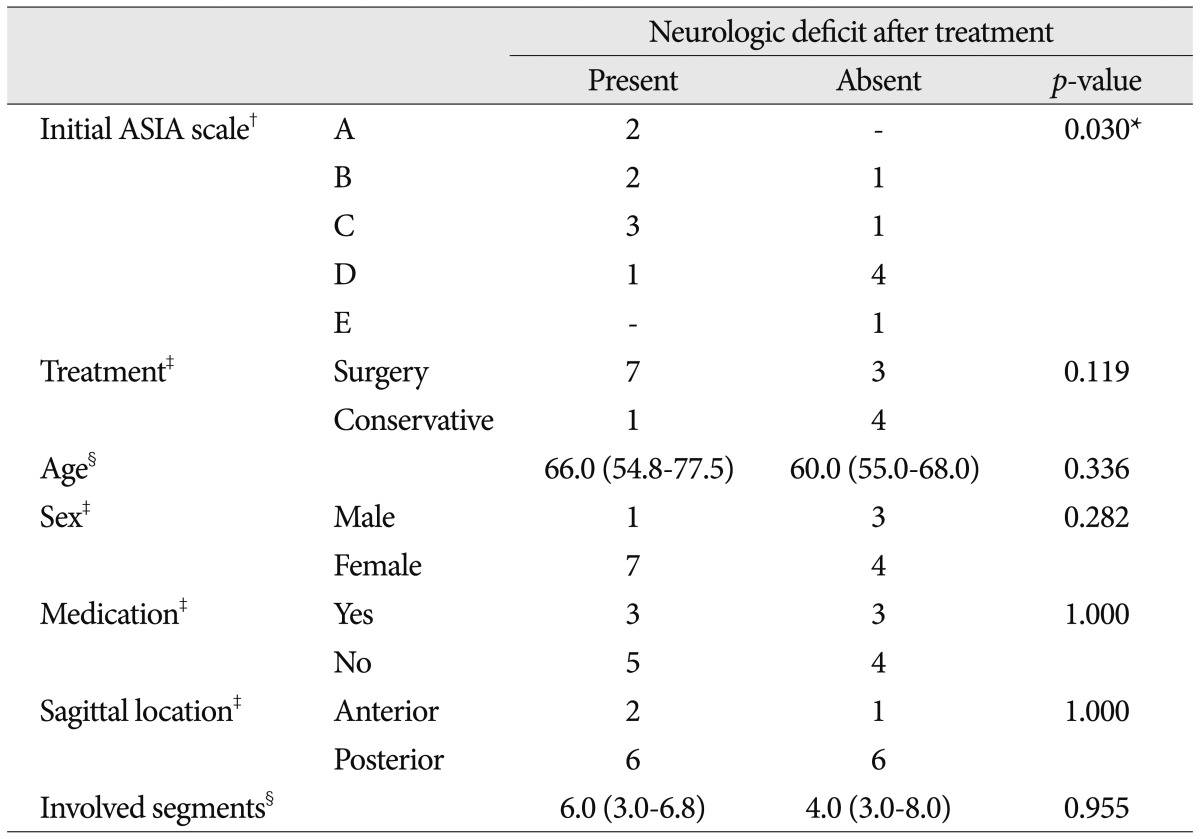

Regardless of treatment methods, normal neurological status (ASIA scale E) after treatment showed a strong relationship with initial ASIA scale (p=0.030). However, there is no significant difference between treatment methods. Patients characteristics such as age, sex, premorbid medication of antiplatelets or anticoagulants did not seem to affect complete recovery. Also, sagittal location and length of involved segments of hematomas did not correlated with neurological recovery. These analyses were summarized in the Table 4.

DISCUSSION

SSEH usually presents with acute symptoms such as neck or back pain, radiating pain, progressive weakness, and cauda equina syndrome due to compression of the spinal cord or nerve roots23). Because these symptoms can mimic a disc herniation, epidural tumor or an infection, differential diagnosis is important. MRI has been currently recognized as the most accurate diagnostic method for establishing a differential diagnosis10,19,27). The MR imaging appearance of SSEH is heterogeneously hyperintense on the T2-weighted MR images and homogeneously isointense on the T1-weighted images. But signals of MR imaging can be varied with the lapse of time. In some cases, T2-weighted images appear as heterogeneously hyperintense and T1-weighted images can range from homogeneously isointense to hyperintense. Most of SSEH do not display enhancement20), however, in the hyperacute stage, the lesion can be enhanced25).

The traditional treatment of choice for SSEH has been surgical treatment such as decompressive laminectomy and hematoma evacuation10,19-21). Many authors emphasize the role of early surgery, especially within 48 hours in cases with incomplete spinal cord dysfunction, or 36 hours for complete spinal cord dysfunction1,11,17,22). Patients with severe neurological deficits preoperatively had poor clinical outcomes2,11,16). Similarly, in the analysis of clinical outcomes of this study, better initial neurological status correlated with an improved clinical outcome.

On the other hand, there are several reports regarding the spontaneous resolution of SSEH without surgery. The authors chose non-surgical treatment in the case of rapid improvement of neurological deficits, inappropriate medical conditions for operation such as coagulopathy, and the refusal of surgery8,10,12,26-28). A literature review revealed that only 10 out of 64 patients treated with conservative management experienced incomplete recovery because they tended to manifest a milder presentation compared to patients with surgical management. However, a literature review revealed no factors that advocate conservative treatment in SSEH10).

A high dose of methylprednisolone was the generally accepted treatment method for acute spinal cord injury3). But, another double blind randomized clinical trial showed no significant difference between the high dose (1000 mg daily) and the low dose (100 mg daily) treatment groups4). In this study, considering the side effects of treatment with a high dose of steroids and the patients' neurologic status, conservative group patients were treated with the low-dose protocol as the equivalent dose of dexamethasone.

Previous studies have reported that the segment involved most frequently in SSEH was the cervicothoracic junction and the sagittal location of the hematoma in the spinal canal was predominantly the dorsal side, which correlates with our results. The posterior internal vertebral venous plexus is bigger and more convoluted than anterior one in the cervicothoracic junction. Furthermore, posterior plexus is uncovered by ligamentous structures. Therefore, it seems to play an important role in the etiology of SSEH6). Others, however, believe arterial rupture as the origin of the hematoma, as the intrathecal pressure is greater than the venous epidural pressure7). Additional risk factors were discussed in several studies such as anticoagulation therapy, antiplatelet drugs, coronary thrombolysis, and hypertension5,13,14,18,29,30). These factors can play an important role in the progression of the hematoma19).

Several reports have stressed the issue that immediate replacement therapy in patients with impaired coagulation prevents progression of the hematoma with improvement of neurological deficits, excluding the need for an operative intervention9). In the present investigation, two patients had been taking aspirin alone, two were treated with aspirin with clopidogrel, one was treated with aspirin with cilostazol and a remaining patient was treated with warfarin. Three of five patients (60.0%) managed conservatively had been taking antiplatelet drugs, but only 3/10 patients (30.0%) in the surgical group took medication. According to Groen et al., in the context of impaired coagulation, a hematoma can remain liquid for a longer period of time when compared to normal clotting, enabling spread of the hematoma into the spinal epidural space. In our study, patients who took antiplatelet drugs or anticoagulants did not tend to present themselves with mild neurological symptoms or exhibit improved clinical outcomes.

Due to the relatively small number of patients, especially in the conservative management group, it is difficult to draw a firm conclusion from this study. To overcome this weak point, nonparametric statistical methods and subgroup analysis were used, but statistical significance may have been overestimated or underestimated due to potential bias with low statistical power. A prospective randomized controlled trial should be performed to identify optimal treatments and therapies. However, there are ethical problems in forcing patients to submit to conservative management when they present progressive neurologic impairment. Furthermore, the rarity of SSEH is a serious obstacle to the design of a new, randomized controlled trial.

CONCLUSION

In the management of patients with SSEH, early decompressive surgical management is usually recommended because the neurologic deficit is mainly caused by compression of the cord and nerve roots by the hematoma. However, conservative management can be considered in patients who present neurologic status as ASIA scale E or in whom early recovery of function has initiated with ASIA scale C or D.