INTRODUCTION

Cavernous malformations are benign vascular lesions of the central nervous system characterized by a mulberry-like cluster of thin-walled vascular sinusoids lined by a thin endothelium, which lacks smooth muscle, elastin, or intervening brain tissue5,16). Cavernous malformations have an annual bleeding incidence of 0.2-2.3%9,10). Most hemorrhages attributable to cavernous malformations are characterized by microhemorrhages and are seldom catastrophic or fatal. Most notably, supratentorial cavernous malformations leading to massive, life-threatening hemorrhages are rare entities4,7). In this report, we describe a case with a supratentorial cavernous malformation resulting in a life-threatening, massive hemorrhage.

CASE REPORT

A 17-year-old female who had no significant prior medical history was brought to the emergency department because of a fall three weeks prior to admission and an increasing state of confusion ever since. Her mental status had reportedly been declining for three weeks. The patient was afebrile, and her physical examination results were unremarkable at the time of admission. A neurological examination revealed a decreased level of consciousness, namely severe confusion, with orientation and cooperation disorders. However, the patient could localize painful stimuli. Her Glasgow Coma Scale score was 10 (E2, M5, V3).

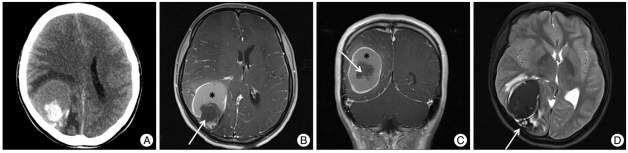

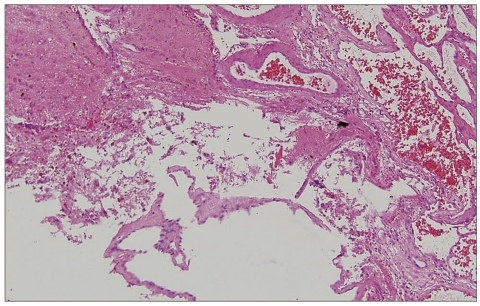

Cranial computerized tomography (CT) revealed a well-circumscribed, 5.5 cm-diameter mass in the right occipital region, causing a midline shift and right lateral ventricle compression (Fig. 1A). The lesion seemed to be composed of a small, hyperdense, acutely hemorrhagic nodule and a large, peripheral, isodense early subacute hematoma. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed that the lesion comprised an acutely hemorrhagic nodule, isointense with deoxyhemoglobin, and a larger subacute hematoma, which was hyperintense due to the presence of methemoglobin (inferred because it was hyperintense on T1-weighted but hypointense on T2-weighted images; Fig. 1B, C). A T2-weighted MRI revealed the classic "popcorn ball" configuration of cavernous malformations at the hematoma's posterior margin (Fig. 1D). Using a right parieto-occipital craniotomy, we evacuated the multi-staged intracerebral hematoma excising a well-circumscribed, purple, lobulated mass consisting of vascular structures in its entirety. Our pathological findings were consistent with a cerebral cavernous malformation (Fig. 2). The patient's post-operative period was uneventful. Her consciousness level was gradually improved, and she was discharged on the ninth post-operative day. A final CT scan at the end of her hospitalization revealed no residual mass (Fig. 3). She returned to her previous occupation as a student, with no neurological deficits, three weeks later.

DISCUSSION

Cavernous malformations have a wide range of presenting symptoms, varying from mild, such as headaches, to more severe symptoms, including seizures, focal neurological deficits, and even death. Epilepsy is the most common clinical manifestation in supratentorial lesions and is seen in 40-50% of such cases1,2,9-11,15). Researchers have ascribed cavernous malformations' epileptogenicity to the deposition of iron and other blood breakdown products6,8). All of the above symptoms can occur with or without acute hemorrhage. Since the definition of "hemorrhage" varies greatly from study to study, the percentage of patients presenting with hemorrhage shows a wide range, from a low of 9% to a high of 88%1,2,15). Reportedly, cavernous malformations have an annual bleeding incidence ranging from 0.2% to 2.3%. Del Curling et al.9) reported symptomatic hemorrhage rates of 0.25% per patient-year and 0.10% per lesion-year. Kim et al.10) reported symptomatic hemorrhage rates of 2.3% per patient-year and 1.4% per lesion-year.

Recently, Washington et al.15) reported on the factors that increase the cavernous malformation hemorrhagic risk. Patients with a previous history of bleeding are at higher risk for a new hemorrhage than are those presenting with incidental findings or with a seizure2,12). In addition, female sex and a family history of hemorrhage increase the risk of bleeding2,14). Furthermore, anatomic location affects the risk. Porter et al.14) reported a higher rate of recurrent symptomatic hemorrhage in infratentorial than in supratentorial lesions (3.8% per patient-year vs. 0.4% per patient-year) and a higher rate in deep than in superficial lesions (4.1% per patient-year vs. 0% per patient-year). Brain stem lesions, in particular, have an aggressive clinical course11).

The indications for, and timing of, cavernous malformations surgery are still unclear. The risk of a significant hemorrhage due to the malformation is relatively low, so hemorrhage prevention should not be an absolute surgical indication. However, clinicians are in general agreement on the need for resection surgery in symptomatic cavernous malformations, particularly for those in superficial, non-eloquent areas. The present case suggests emergency surgery may be necessary in patients with unstable clinical conditions and/or with lesions causing a significant mass effect. Radiosurgery remains controversial, and clinicians require more data to evaluate its efficacy.

Although almost all cavernous malformation cases experience microhemorrhages, such bleeding rarely leads to clinical symptoms. Since these lesions have small diameters and low flow rates, they rarely cause life-threatening intracerebral hematomas13). Zimmerman et al.17) reported one patient who died from rehemorrhage of a tectal cavernous malformation. There are consequences, however, even of repeated small hemorrhages. In our case, we can also suspect rehemorrhage on the basis of various radiologic findings. Nevertheless, our case lacked a previous history of headaches, epilepsy, or neurological deficits but presented with a massive intracerebral hemorrhage from a small, superficially-located supratentorial cavernous malformation. To our knowledge, only one case of massive intracerebral hemorrhage from a supratentorial cavernous malformation has been reported previously3). Unlike our case, it resulted from a giant cavernous malformation, 42├Ś35 mm. Thus, ours is the first report of a massive intracerebral hematoma resulting from a small, superficially-located, supratentorial cavernous malformation.